17 VISUAL APPEALS

ELIZABETH PORTER︎︎︎

By long tradition, law is cerebral, rather than emotional; it is a field of words, not pictures. But this black-and-white understanding of the law—always an oversimplification—is now being directly challenged by the rising influence of visual media in written legal documents. Most of the public discussion of this phenomenon has focused on the role of body camera or other video footage of police activity, often in the context of jury proceedings. But parties and courts are now embedding images into written legal documents in a far broader range of contexts. These images may appear natural and innocuous. After all, we live in a multimedia digital universe. In that very naturalness lies their power, and their potential for abuse. My research aims to uncover this new phenomenon that is quietly and colorfully transforming legal discourse.

In Scott v. Harris in 2007, the Supreme Court embedded a video link into an opinion for the first time—the link to a dash-cam video of a police chase. In an 8-1 decision, the Court dismissed an excessive force case against a police officer, finding that the video made it “clear” that the officer’s conduct did not violate the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution. The Court’s finding in Scott contradicted two lower court decisions holding that a jury (and not a court) should assess the reasonableness of the officer’s actions. In addition to the link in the opinion, the Scott footage may be viewed on YouTube here. Scott prompted questions about the potential for images to circumvent the traditional purview of the jury.

But the emerging use of images in legal documents extends far beyond police camera footage. To take a recent example: Timothy Foster was convicted of murder in 1987 and sentenced to death by an all-white jury in Georgia. During jury selection, the prosecution had used its peremptory strikes to exclude all four black prospective jurors. Almost thirty years later, in 2016, the Supreme Court overturned Foster’s death sentence, finding that the prosecution had intentionally excluded black citizens from the jury during the selection process in violation of the Constitution.

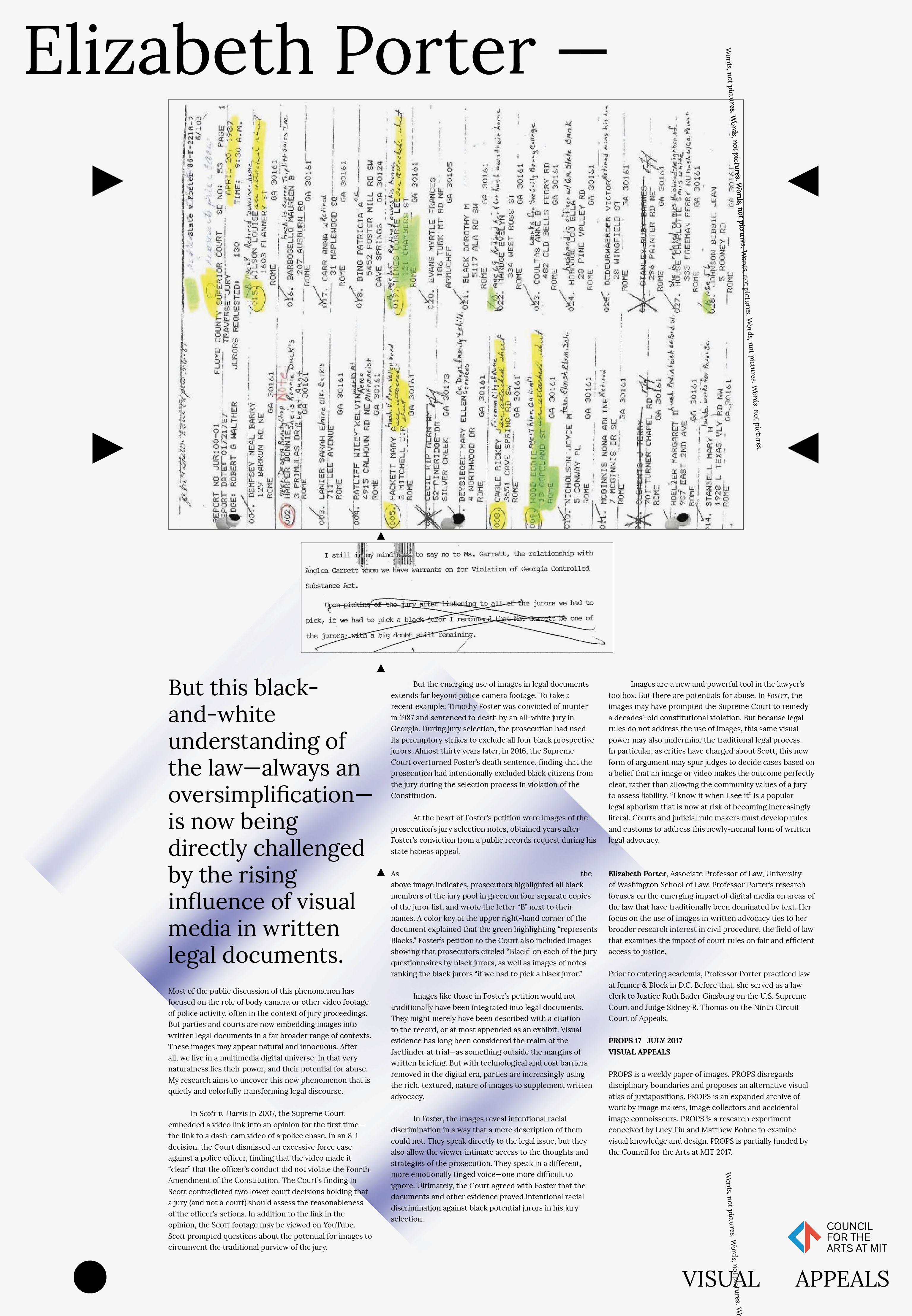

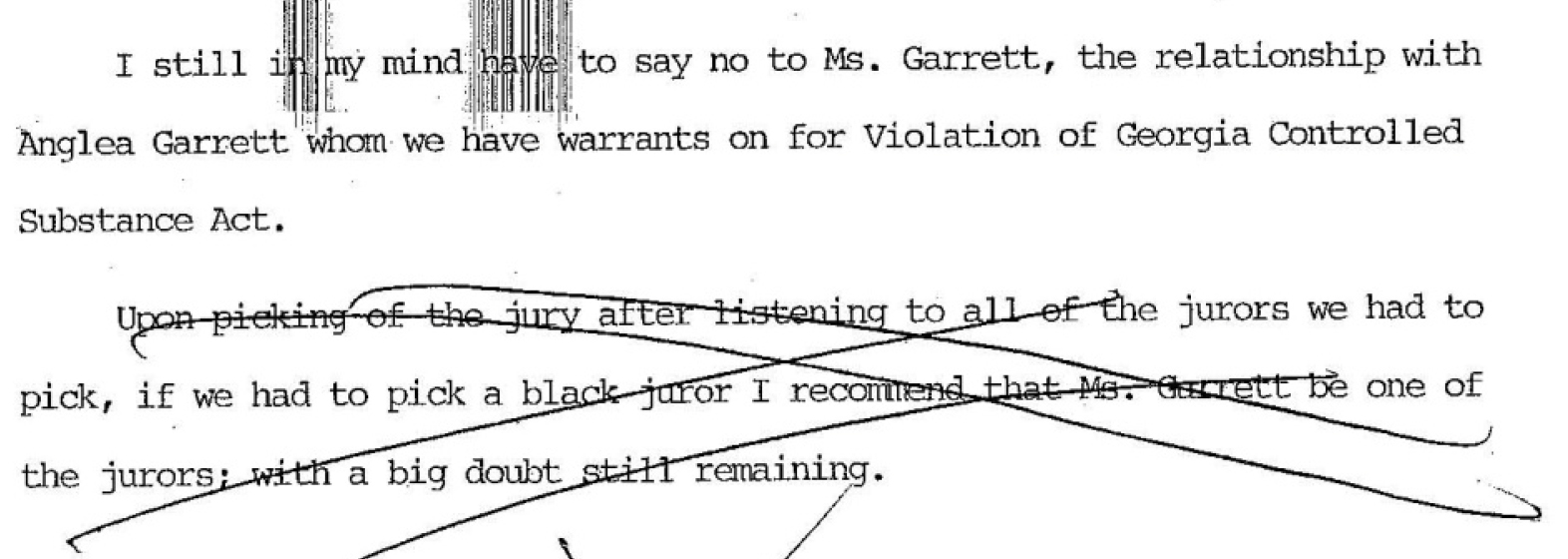

At the heart of Foster’s petition were images of the prosecution’s jury selection notes, obtained years after Foster’s conviction from a public records request during his state habeas appeal.

By long tradition, law is cerebral, rather than emotional; it is a field of words, not pictures. But this black-and-white understanding of the law—always an oversimplification—is now being directly challenged by the rising influence of visual media in written legal documents. Most of the public discussion of this phenomenon has focused on the role of body camera or other video footage of police activity, often in the context of jury proceedings. But parties and courts are now embedding images into written legal documents in a far broader range of contexts. These images may appear natural and innocuous. After all, we live in a multimedia digital universe. In that very naturalness lies their power, and their potential for abuse. My research aims to uncover this new phenomenon that is quietly and colorfully transforming legal discourse.

In Scott v. Harris in 2007, the Supreme Court embedded a video link into an opinion for the first time—the link to a dash-cam video of a police chase. In an 8-1 decision, the Court dismissed an excessive force case against a police officer, finding that the video made it “clear” that the officer’s conduct did not violate the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution. The Court’s finding in Scott contradicted two lower court decisions holding that a jury (and not a court) should assess the reasonableness of the officer’s actions. In addition to the link in the opinion, the Scott footage may be viewed on YouTube here. Scott prompted questions about the potential for images to circumvent the traditional purview of the jury.

But the emerging use of images in legal documents extends far beyond police camera footage. To take a recent example: Timothy Foster was convicted of murder in 1987 and sentenced to death by an all-white jury in Georgia. During jury selection, the prosecution had used its peremptory strikes to exclude all four black prospective jurors. Almost thirty years later, in 2016, the Supreme Court overturned Foster’s death sentence, finding that the prosecution had intentionally excluded black citizens from the jury during the selection process in violation of the Constitution.

At the heart of Foster’s petition were images of the prosecution’s jury selection notes, obtained years after Foster’s conviction from a public records request during his state habeas appeal.

As Image One indicates, prosecutors highlighted all black members of the jury pool in green on four separate copies of the juror list, and wrote the letter “B” next to their names. A color key at the upper right-hand corner of the document explained that the green highlighting “represents Blacks.” Foster’s petition to the Court also included images showing that prosecutors circled “Black” on each of the jury questionnaires by black jurors, as well as images of notes ranking the black jurors “if we had to pick a black juror.”

Images like those in Foster’s petition would not traditionally have been integrated into legal documents. They might merely have been described with a citation to the record, or at most appended as an exhibit. Visual evidence has long been considered the realm of the factfinder at trial—as something outside the margins of written briefing. But with technological and cost barriers removed in the digital era, parties are increasingly using the rich, textured, nature of images to supplement written advocacy.

In Foster, the images reveal intentional racial discrimination in a way that a mere description of them could not. They speak directly to the legal issue, but they also allow the viewer intimate access to the thoughts and strategies of the prosecution. They speak in a different, more emotionally tinged voice—one more difficult to ignore. Ultimately, the Court agreed with Foster that the documents and other evidence proved intentional racial discrimination against black potential jurors in his jury selection.

Images are a new and powerful tool in the lawyer’s toolbox. But there are potentials for abuse. In Foster, the images may have prompted the Supreme Court to remedy a decades’-old constitutional violation. But because legal rules do not address the use of images, this same visual power may also undermine the traditional legal process. In particular, as critics have charged about Scott, this new form of argument may spur judges to decide cases based on a belief that an image or video makes the outcome perfectly clear, rather than allowing the community values of a jury to assess liability. “I know it when I see it” is a popular legal aphorism that is now at risk of becoming increasingly literal. Courts and judicial rule makers must develop rules and customs to address this newly-normal form of written legal advocacy.

ELIZABETH PORTER︎︎︎ is an Associate Professor of Law, University of Washington School of Law. Professor Porter’s research focuses on the emerging impact of digital media on areas of the law that have traditionally been dominated by text. Her focus on the use of images in written advocacy ties to her broader research interest in civil procedure, the field of law that examines the impact of court rules on fair and efficient access to justice.

Prior to entering academia, Professor Porter practiced law at Jenner & Block in D.C. Before that, she served as a law clerk to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the U.S. Supreme Court and Judge Sidney R. Thomas on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.