10 DRY SALVAGES

FRANÇOIS LANUSSE︎︎︎

To a cosmologist like me, imaging the night sky through powerful telescopes opens an invaluable yet indirect window into the content of our Universe. Why indirect? Because the billions of galaxies that we do observe are just the tip of the iceberg. They are sprinkled onto a massive underlying cosmic web of dark matter that, despite accounting for most of the total matter of the Universe, is completely invisible. Its presence is betrayed by its gravitational effects. In particular, very massive dark matter structures effectively act as gravitational lenses, distorting the images of objects located behind them, much like objects are distorted and magnified if you look at them through a magnifying glass. Although this lensing effect is generally very small, it is ubiquitous on the sky - virtually every galaxy that we see is actually being lensed by some amount.

This is where images play a crucial role in the science that I do. By taking images of millions of galaxies (and even billions in the near future) and precisely measuring their shapes, we can detect the deformations caused by gravitational lensing, and from there infer the distribution of dark matter. But with such a small effect, devil is in the details. Great care must be taken in the acquisition and processing of these images as to not introduce any additional deformations, which would otherwise bias our analysis down the road. In order to detect and correct for any errors in this delicate measurement process, we rely on complex simulations of galaxy images that aim to mimic as closely as possible how real galaxies would be observed by our telescopes.

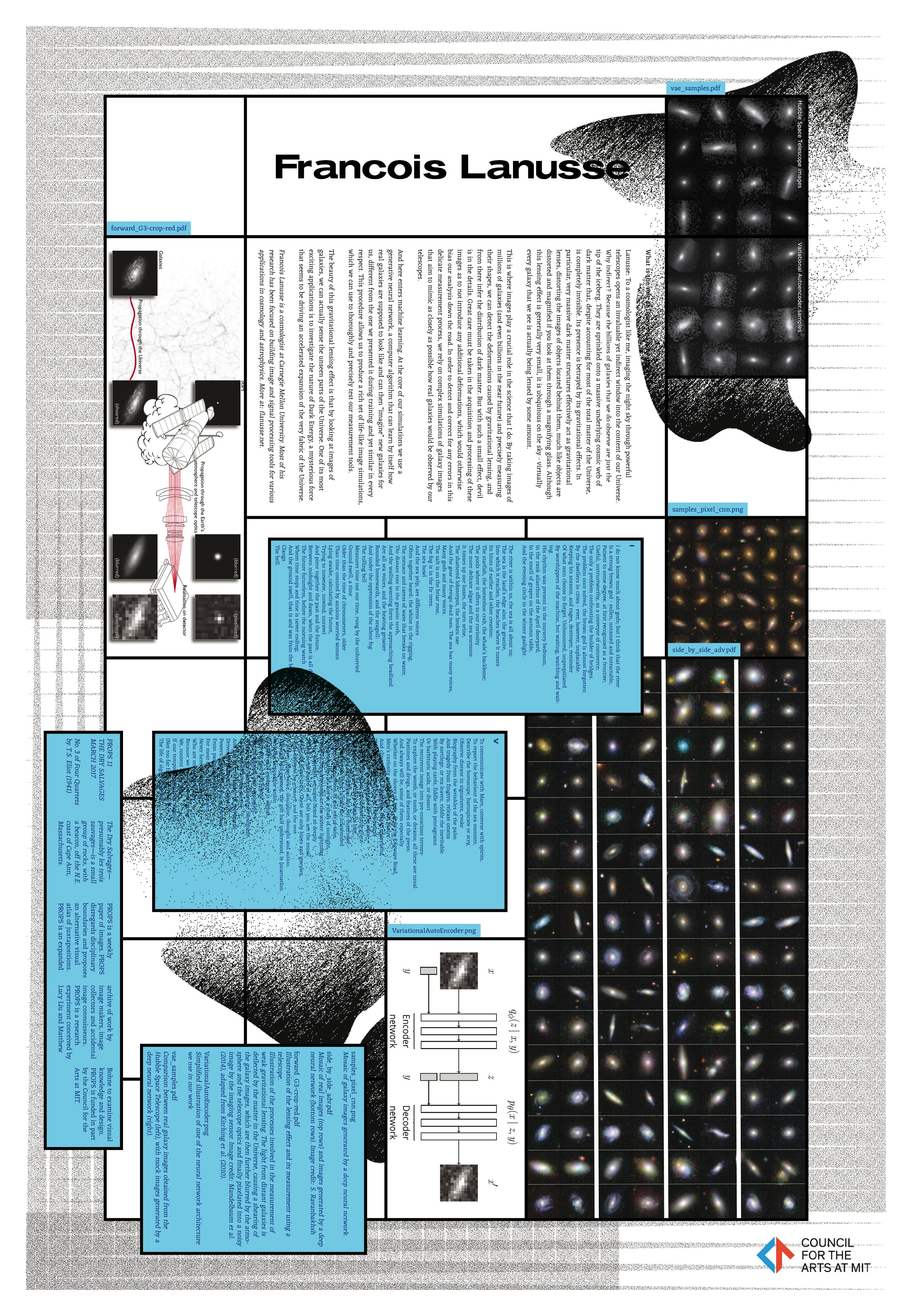

And here enters machine learning. At the core of our simulations we use a generative neural network, a computer algorithm that can learn by itself how real galaxies are supposed to look like and can then "imagine" new galaxies for us, different from the one we presented it during training and yet similar in every respect. This procedure allows us to produce a rich set of life-like image simulations, which we can use to thoroughly and precisely test our measurement tools.

The beauty of this gravitational lensing effect is that by looking at images of galaxies, we can actually sense the unseen parts of the Universe. One of its most exciting applications is to investigate the nature of Dark Energy, a mysterious force that seems to be driving an accelerated expansion of the very fabric of the Universe.

FRANÇOIS LANUSSE︎︎︎ is a cosmologist at Carnegie Mellon University. Most of his research has been focused on building image and signal processing tools for various applications in cosmology and astrophysics.

Further reading on artificial intelligence and galaxies: "Astronomers explore uses for AI-generated imagesNeural networks produce pictures to train image-recognition programs and scientific software."

To a cosmologist like me, imaging the night sky through powerful telescopes opens an invaluable yet indirect window into the content of our Universe. Why indirect? Because the billions of galaxies that we do observe are just the tip of the iceberg. They are sprinkled onto a massive underlying cosmic web of dark matter that, despite accounting for most of the total matter of the Universe, is completely invisible. Its presence is betrayed by its gravitational effects. In particular, very massive dark matter structures effectively act as gravitational lenses, distorting the images of objects located behind them, much like objects are distorted and magnified if you look at them through a magnifying glass. Although this lensing effect is generally very small, it is ubiquitous on the sky - virtually every galaxy that we see is actually being lensed by some amount.

This is where images play a crucial role in the science that I do. By taking images of millions of galaxies (and even billions in the near future) and precisely measuring their shapes, we can detect the deformations caused by gravitational lensing, and from there infer the distribution of dark matter. But with such a small effect, devil is in the details. Great care must be taken in the acquisition and processing of these images as to not introduce any additional deformations, which would otherwise bias our analysis down the road. In order to detect and correct for any errors in this delicate measurement process, we rely on complex simulations of galaxy images that aim to mimic as closely as possible how real galaxies would be observed by our telescopes.

And here enters machine learning. At the core of our simulations we use a generative neural network, a computer algorithm that can learn by itself how real galaxies are supposed to look like and can then "imagine" new galaxies for us, different from the one we presented it during training and yet similar in every respect. This procedure allows us to produce a rich set of life-like image simulations, which we can use to thoroughly and precisely test our measurement tools.

The beauty of this gravitational lensing effect is that by looking at images of galaxies, we can actually sense the unseen parts of the Universe. One of its most exciting applications is to investigate the nature of Dark Energy, a mysterious force that seems to be driving an accelerated expansion of the very fabric of the Universe.

FRANÇOIS LANUSSE︎︎︎ is a cosmologist at Carnegie Mellon University. Most of his research has been focused on building image and signal processing tools for various applications in cosmology and astrophysics.

Further reading on artificial intelligence and galaxies: "Astronomers explore uses for AI-generated imagesNeural networks produce pictures to train image-recognition programs and scientific software."