07 POLYPLASMICPOLITICS

LÉOPOLD LAMBERT︎︎︎

In my research, I am interested in images, not as mere illustrations but, rather in their potentiality to act as evidence. By this, I do not mean that images reveal the truth of a situation but, rather, that they can bring some matter to a subjective and political interpretation of reality: a truth if we may say.

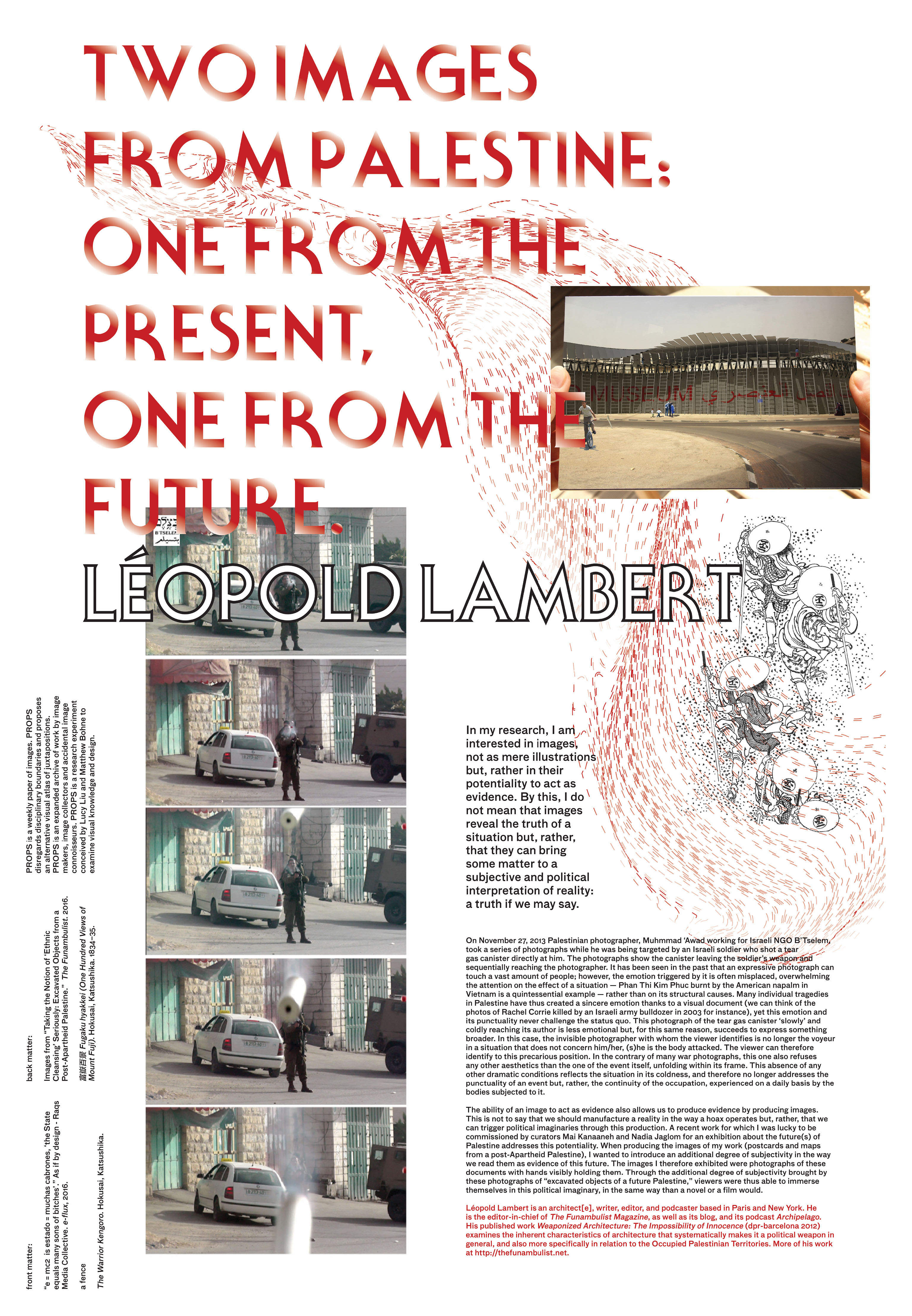

On November 27, 2013 Palestinian photographer, Muhmmad ‘Awad working for Israeli NGO B’Tselem, took a series of photographs while he was being targeted by an Israeli soldier who shot a tear gas canister directly at him. The photographs show the canister leaving the soldier’s weapon and sequentially reaching the photographer. It has been seen in the past that an expressive photograph can touch a vast amount of people; however, the emotion triggered by it is often misplaced, overwhelming the attention on the effect of a situation — Phan Thi Kim Phuc burnt by the American napalm in Vietnam is a quintessential example — rather than on its structural causes. Many individual tragedies in Palestine have thus created a sincere emotion thanks to a visual document (we can think of the photos of Rachel Corrie killed by an Israeli army bulldozer in 2003 for instance), yet this emotion and its punctuality never challenge the status quo. This photograph of the tear gas canister ‘slowly’ and coldly reaching its author is less emotional but, for this same reason, succeeds to express something broader. In this case, the invisible photographer with whom the viewer identifies is no longer the voyeur in a situation that does not concern him/her, (s)he is the body attacked. The viewer can therefore identify to this precarious position. In the contrary of many war photographs, this one also refuses any other aesthetics than the one of the event itself, unfolding within its frame. This absence of any other dramatic conditions reflects the situation in its coldness, and therefore no longer addresses the punctuality of an event but, rather, the continuity of the occupation, experienced on a daily basis by the bodies subjected to it.

The ability of an image to act as evidence also allows us to produce evidence by producing images. This is not to say that we should manufacture a reality in the way a hoax operates but, rather, that we can trigger political imaginaries through this production. A recent work for which I was lucky to be commissioned by curators Mai Kanaaneh and Nadia Jaglom for an exhibition about the future(s) of Palestine addresses this potentiality. When producing the images of my work (postcards and maps from a post-Apartheid Palestine), I wanted to introduce an additional degree of subjectivity in the way we read them as evidence of this future. The images I therefore exhibited were photographs of these documents with hands visibly holding them. Through the additional degree of subjectivity brought by these photographs of “excavated objects of a future Palestine,” viewers were thus able to immerse themselves in this political imaginary, in the same way than a novel or a film would.

LÉOPOLD LAMBERT︎︎︎ is an architect[e], writer, editor, and podcaster based in Paris and New York. He is the editor-in-chief of The Funambulist Magazine, as well as its blog, and its podcast Archipelago. His published work Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence (dpr-barcelona 2012) examines the inherent characteristics of architecture that systematically makes it a political weapon in general, and also more specifically in relation to the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

In my research, I am interested in images, not as mere illustrations but, rather in their potentiality to act as evidence. By this, I do not mean that images reveal the truth of a situation but, rather, that they can bring some matter to a subjective and political interpretation of reality: a truth if we may say.

On November 27, 2013 Palestinian photographer, Muhmmad ‘Awad working for Israeli NGO B’Tselem, took a series of photographs while he was being targeted by an Israeli soldier who shot a tear gas canister directly at him. The photographs show the canister leaving the soldier’s weapon and sequentially reaching the photographer. It has been seen in the past that an expressive photograph can touch a vast amount of people; however, the emotion triggered by it is often misplaced, overwhelming the attention on the effect of a situation — Phan Thi Kim Phuc burnt by the American napalm in Vietnam is a quintessential example — rather than on its structural causes. Many individual tragedies in Palestine have thus created a sincere emotion thanks to a visual document (we can think of the photos of Rachel Corrie killed by an Israeli army bulldozer in 2003 for instance), yet this emotion and its punctuality never challenge the status quo. This photograph of the tear gas canister ‘slowly’ and coldly reaching its author is less emotional but, for this same reason, succeeds to express something broader. In this case, the invisible photographer with whom the viewer identifies is no longer the voyeur in a situation that does not concern him/her, (s)he is the body attacked. The viewer can therefore identify to this precarious position. In the contrary of many war photographs, this one also refuses any other aesthetics than the one of the event itself, unfolding within its frame. This absence of any other dramatic conditions reflects the situation in its coldness, and therefore no longer addresses the punctuality of an event but, rather, the continuity of the occupation, experienced on a daily basis by the bodies subjected to it.

The ability of an image to act as evidence also allows us to produce evidence by producing images. This is not to say that we should manufacture a reality in the way a hoax operates but, rather, that we can trigger political imaginaries through this production. A recent work for which I was lucky to be commissioned by curators Mai Kanaaneh and Nadia Jaglom for an exhibition about the future(s) of Palestine addresses this potentiality. When producing the images of my work (postcards and maps from a post-Apartheid Palestine), I wanted to introduce an additional degree of subjectivity in the way we read them as evidence of this future. The images I therefore exhibited were photographs of these documents with hands visibly holding them. Through the additional degree of subjectivity brought by these photographs of “excavated objects of a future Palestine,” viewers were thus able to immerse themselves in this political imaginary, in the same way than a novel or a film would.

LÉOPOLD LAMBERT︎︎︎ is an architect[e], writer, editor, and podcaster based in Paris and New York. He is the editor-in-chief of The Funambulist Magazine, as well as its blog, and its podcast Archipelago. His published work Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence (dpr-barcelona 2012) examines the inherent characteristics of architecture that systematically makes it a political weapon in general, and also more specifically in relation to the Occupied Palestinian Territories.